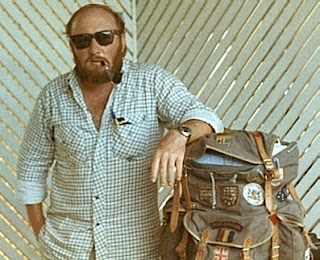

With kind permission by Dermott Ryder

For the previous instalment of Dermott's story, click here.

For the more conservative members of the expatriate community there were other diversions. Outdoor pursuits including bird watching, fishing and beach combing were popular. For those built for comfort and the intellectuals, card games, backgammon and chess did the trick. Inevitably, I suppose, I started a guitar circle with unaccompanied singing and poetry thrown in when available. To gather a group of interested people I simply sat on the veranda every evening and played and sang a few songs, boredom and curiosity did the rest.

The expatriates attracted to the circle were a diverse bunch. USA, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, Spain, France and Germany were all, over time, represented. Their differences at times were striking but they all had something in common, the need for creative social intercourse.

The group was as anarchic as it was organic. It evolved simply by being. Guitar accompanied singing was readily acceptable but at first unaccompanied singing and poetry that didn't rhyme attracted a little derision. Poetry that did rhyme but lacked the required level of obscenity also struggled for acceptance. Eventually, in a surprisingly short time, the half remembered party pieces and ribald rugby songs of some members gave way to more considered offerings.

I was not surprised by the enthusiasm for reading established poets works or by the interest in both contemporary and traditional folksong. What did surprise me was the amount of admirable original work presented, hesitantly at first but with growing eagerness. Within this environment I felt confident to present my own Bougainville generated work.

The single greatest enemy on the Bougainville coast was the climate. The heat and humidity formed a devastating partnership. From the lowly leather watchstrap through to the most robust equipment, just about everything disintegrated in next to no time. Musical instruments were especially vulnerable: guitars, banjos and fiddles all suffered terribly. The only concertina I encountered fell apart in mid-performance. I tried to counter the conditions by cleaning and polishing my steel string guitar, including the strings, almost daily. When my guitar cleaning kit ran out I resorted to spray-on furniture polish.

My guitar survived the Bougainville experience. Others were not so lucky. A classical player at a formal musical evening had an unfortunate experience. Seated in the appointed position - right foot on little metal footrest, guitar between thighs and fret board pointing upward towards the left ear - he started slowly then he got into it with a passion. With his left hand flying up and down the frets and his right hand clawing and thrashing at the strings he achieved the climax with a flourish. He graciously accepted a flutter of applause. At that moment the guitar's bridge gave up the unequal struggle between passion, percussion, the Bougainville climate and glue designed to serve in temperate conditions. The bridge broke loose with a tortured, rattling boing and struck him on the nose, or thereabouts.

This must have embarrassed and humiliated the virtuoso beyond measure. He lost it. He kicked his little metal footrest out into the Bougainville night. Then gripping his extremely expensive guitar by the fret board he smashed it to bits against a coconut tree conveniently growing near the performance space. At this point the organizer of the musical evening, acting as MC, suggested we all have a short break.

Meanwhile, back on the job... As the contract wound down the distant rulers of the company ordered local management to cut the indigenous head count. Sadly, in remote area construction, this is an inevitable step in the final stages of a job as it moves towards completion.

Separating people from gainful employment needs careful handling, a humane approach. Unfortunately, neither the project manager nor the general foremen were human nor were their methods humane. They simply tore several pages from the record book and issued the instruction for summary execution.

We, the rational ones, the unofficial underground movement, found this approach unacceptable but at first thought that we could do little to change it. Then a plan presented itself.� Mail security being non-existent we easily acquired the authorised list and confirmed that it included the names of many of our most reliable workers. We removed those names and to make up the required number we replaced them with the names of non-existent workers, known payroll ghosts. It was the work of moments and the adjusted mail went its merry way on time.

It all worked well. Instead of losing many workers we only lost a few. The head office accountants registered a worthwhile cost saving and, at the same time, we struck a blow to the hip-pocket nerve of the avaricious ungodly.

This substitution went unnoticed for a fortnight, the indigenous workers pay period, then all hell broke loose, albeit in a suppressed, red faced, swearing, spitting, door slamming way. I wish I could have been a fly on the wall when certain privileged people discovered that the pay of the ghosts, a lucrative cash perquisite, was lost to them forever because some son of a bitch had removed the ghosts from the payroll by including them on a termination list. It must have been truly galling to be unable to re-establish the ghosts because at a labour shedding stage of contract how could they possibly hire new workers, even if they were invisible. Somebody would notice. Somebody would ask questions.

Meanwhile, the world was once again closing in on Bougainville. Time and tide and the coming of the vainglorious Gough Whitlam and his posse of political poseurs, including the flamboyant Bob Hawke and the super-trendy Jim Cairns, marked yet another turning point in the lives and fortunes of numerous tribes of the External Territories.

Whitlam, with an imperious wave of his chubby hand, offered the people a bright and wonderful future under the paternal rule of the Australian Labor Party. He also added, 'in time I will bring freedom, self-determination and self rule to the people of TPNG'. Strangely enough he didn't mention the violence, corruption and social dislocation that would follow in the wake of the abject failure of his personal dreams of glory and of his short but eventful time in government.

My time to leave Bougainville was at hand. The project manager and the general foreman recommended to our masters in Port Moresby the withdrawal of my expatriate guarantee bond. They had no provable cause to do this, beyond deep suspicion and festering paranoia. They came to the belief that I had played a part in the ghost busting - though did not say so publicly - so the general foreman accused me of having a hand in 'fermenting revolt' by the distribution of too many bread rolls and tins of pilchards in tomato sauce to the workers at lunch breaks. A fascinatingly ludicrous idea that still fills me with contempt for my erstwhile employers and for those self-serving despots placed above us in the service of the company.

If native labourers working twelve hours a day, six days a week for a pittance and a meal of tinned fish and bread rolls isn't exploitation I don't know what is. We, the so-called protecting powers, did not do the peoples of the External Territories any favours.

I gave the workers a few extra tins of fish and bread rolls � so what! How could such an act do anything other than assuage hunger? As for fermenting revolt, that process inevitably occurs as a direct result of a colonial power existing.

Without the expatriate guarantee bond I was persona non grata in the external territories. However, I was cashed up and ready to go. It was time to move on. During the expedited preparations for my departure I discovered an ally, none other than the expatriate administration clerk with a number of serious issues. When the dark powers discovered the great ghost extraction he was a prime suspect.

He loudly and convincingly protested his innocence but in the cross-examination he had taken a brutal, verbal lashing from the interrogators. He too thirsted for revenge so as part of his evil and largely unshared plan he lost the paperwork requesting the revocation of my bond and provided me with air ticketing that allowed me to travel the length and breadth of Papua New Guinea.

I revisited Rabaul, New Britain, one of my favourite places. They knew me by name at the Kaivuna Motel. Sadly, this pleasant, historic little town, after a decade of fear, suffered a catastrophic volcanic eruption in 1994.

I also, after a short flight, attended my last boozy party at the Ansett Lodge in Lae, TPNG before setting out on an around the mountains trip via Goroka, Madang and Wewak to Mount Hagen and eventually to Port Moresby - and then, on to Australia.